Timber Tales: Lumbering and lumber camps in Michigan

We often think of Michigan as a manufacturing powerhouse, but before that it was a major source for the raw materials that nineteenth-century America needed most: copper, iron, salt, and especially lumber.

Pine trees, especially white pine, were the most valuable because they were the best for making furniture. Early estimates suggested there might be 150 billion feet of pine wood in Michigan, but the final number was much higher.

Most of the wood harvested in the early nineteenth century came from the forests along the East Coast, especially Maine. But by the 1840s, lumber companies were looking for new sources of wood, and many of them moved their operations to Saginaw Bay. Rivers flowing into the bay gave the logging companies access to hundreds of miles of stands, and Saginaw became a major center for lumber in the 1850s. On the western side of the state Muskegon became an even larger apex and as Willis Dunbar notes, “second only to Chicago among Lake Michigan ports.”

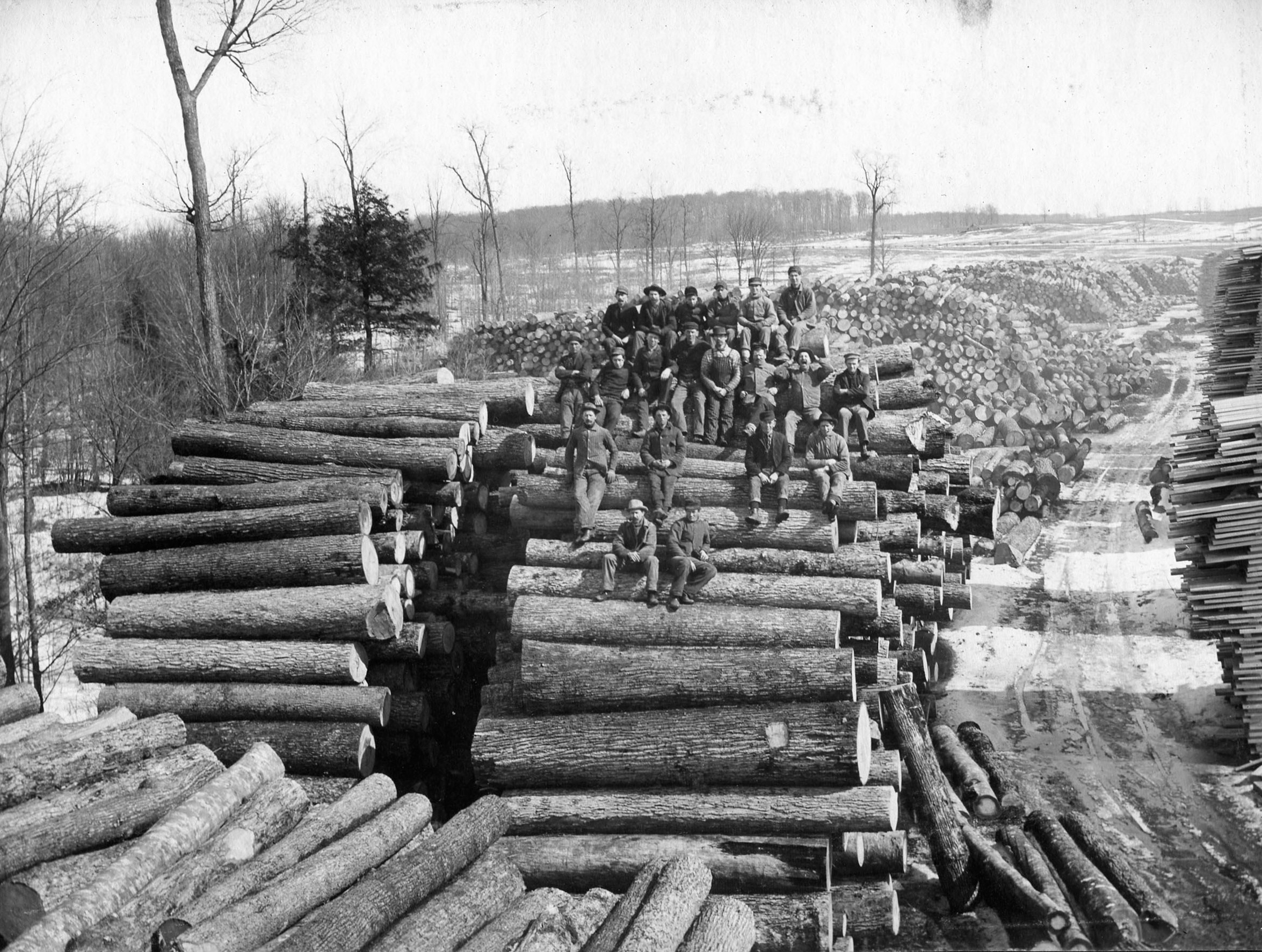

Logging in the mid-19th century was limited to the winter months, when sleds could carry logs over the snow to nearby rivers. In the spring, heavy rainfall would cause rivers to rise and make it easier to transport logs downstream to sawmills built near river mouths. Once they reached the sawmill logs would be stored in "booms," organized by company.

In the 1870s over a dozen railroads gave loggers access to more remote stands of pine, and by the end of the century the companies had taken over 160 billion feet of pine wood. Around the same time, sawmills moved from water to steam-power. (Great Lakes Informant, pp 2-3), and bandsaws replaced circular saws in the 1880s. (Great Lakes Informant, pp 2-3)

Things were changing out in the logging camps too. Cross-cut saws replaced axes and horses replaced oxen. (Great Lakes Informant, pp 2-3)

Big Wheels (invented by Cyrus Overpack of Manistee) made it possible to transport logs the rest of the year, and narrow gauge railroads were a cost-effective way to build temporary rail lines were a cost-effective and more flexible alternative to rivers (though they never fully replaced them). (Great Lakes Informant, pp 2-3)

Lumber in 1860s-1890s brought millions to the state but led to rise and quick fall of several small communities (Great Lakes Informant, p 4)

Where loggers came from, including Scandinavia (Great Lakes Informant, p 3) Unionization (Great Lakes Informant, p 3)

Environmental impact. How pine-harvested land left behind by loggers failed small farmers, but then became the core of federal parks (Great Lakes Informant, pp 3-4)

ending

.